By Grace Renshaw

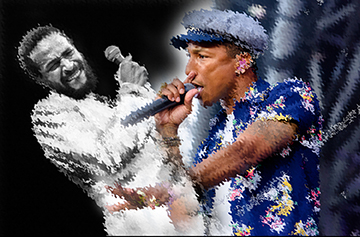

Daniel Gervais and Joe Fishman agree that Williams v. Gaye, a long-running case challenging a copyright infringement claim brought by the estate of the late singer-songwriter Marvin Gaye against performers Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke, has created more problems than it solves.

Both scholars are amply qualified to critique the jury verdict in Williams v. Gaye, also known as the “Blurred Lines” case. Gervais holds the Milton R. Underwood Chair in Law and directs Vanderbilt’s Intellectual Property Program; he recently wrote a book proposing a comprehensive path to international copyright reform. Fishman, an associate professor who studies copyright and intellectual property law, found the “Blurred Lines” decision so frustrating that he wrote a Harvard Law Review article, “Music as a Matter of Law,” to explain exactly how the case continued to muddle the definition of “music” for copyright purposes, creating uncertainty for future composers.

Both scholars point to two reasons the outcome in Williams v. Gaye—a $5.3 million judgment in favor of the Gaye estate—was so problematic: It was a jury trial, and the accused infringers were poorly prepared and came off as arrogant. Thicke reportedly admitted to the copying before the trial. Yet, confident of an easy victory, Williams and Thicke filed suit for declaratory judgment that their song, “Blurred Lines,” did not infringe on the copyright of Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” after Gaye’s heirs demanded a share of the profits when the song became a megahit in 2013. The case ended up in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California. “It’s possible the jury simply wanted Robin Thicke to lose,” Gervais said.

But the major issue, Fishman explains, is that the Williams decision, recently upheld by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, has increased uncertainty for songwriters and composers seeking to produce original work. To the jury, the two songs sounded very similar. However—crucially—their melodies were different. “Until recently, courts essentially looked at melody alone as the protectable part of a musical work,” Fishman explained. “They weren’t interested in orchestration, percussion, the structure of a piece or tone quality. Courts emphasized melody because they thought it was the most important part of a musical work. Courts appeared to think that, aesthetically, the heart of a piece of music was its melody, because they believed that’s what caused listeners to buy an album or a ticket to a concert.”

Historically, courts’ application of melody as the differentiating factor in a piece of music had an advantage for music composers, according to Fishman: It provided a clear boundary for composers that was lacking in other areas of copyright. “Most copyright infringement cases outside of music since the beginning of the 20th century applied a grab bag of different elements that could sustain an infringement action if they were copied, because there’s no single defining element you can point to in art or literature,” he said.

When Gaye’s estate convinced the judge to let the “Blurred Lines” case reach a jury, the resulting, high-visibility decision legitimized a trend toward applying a broader definition of music to copyright claims. Music composers had previously relied on years of legal precedent that writing a different melody was a sure strategy to avoid infringement. “Blurred Lines” now forced them to confront the fact that courts were now applying a broader definition of music by considering additional composition elements in deciding music copyright cases.

Protect Professional Creators

Gervais believes copyright law faces an enormous challenge in an era when anyone can record and distribute a song, publication or artworks. “The copyright system was created for professionals—professional authors, journalists, people who would try to dedicate their careers to composing music, writing, art or film production,” he explained. “That has been completely upended.”

Intellectual property law, Gervais contends, hasn’t evolved fast enough to address rapid technological advancement, globalization and the easy availability of an endless array of content online. While he acknowledges some amateur content may have value, Gervais stresses the importance of protecting professional work. “Not all informational and cultural products created by professionals are of high quality, but almost all high-quality products are created by professionals,” he said. “When anybody can publish anything, it’s almost impossible for professionals to continue. If we don’t find a solution to copyright, we’re not only going to lose creative professionals, but the impact on culture, information and ultimately democracy, may be irreversible.”

He sees the glut of nonprofessional content as particularly problematic for journalists. “Democracy doesn’t work very well without professional journalists, and there are arguably only two independent national newspapers left in the U.S.,” he said.

Gervais is also concerned about the new questions the advent of artificial intelligence will present for attorneys in every area of law, including intellectual property. “Most lawyers will likely encounter something having to do with AI or robots in the next 10 to 15 years,” he said. He is developing a new class for 2019: Robots, Artificial Intelligence and the Law, aimed at anticipating challenges to the legal order such as the Arizona woman killed by a self-driving car in March. “The class will cover everything from contracts to torts to IP to international law to the law of war,” he said.

Shaping Copyright Policy

Aurelia Schultz ’09 called it “extreme providence” that Gervais—an expert in international intellectual property law—arrived at Vanderbilt in time for her 2L year. Certain she wanted to practice international property law, she took his classes in Intellectual Property and International IP along with classes in Patent Law and a Trademark Law class taught by Third Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Kent Jordan. Schultz now works as a counsel for policy and international affairs at the U.S. Copyright Office in Washington, D.C., having previously worked for several years with Creative Commons, a nonprofit that offers authors, artists, photographers and other creative professionals around the world copyright licenses they can use to protect and share their intellectual property.

At Creative Commons, Schultz built a team tasked with tailoring open-access tools aimed at educating creators in eight African nations about intellectual property and helping them share their work. She understood the nuances of working in Africa, having served two years in Zambia with the Peace Corps before law school and spent a semester as a legal intern with the Nigerian Copyright Commission while earning her J.D. “I actually came into law school wanting to do intellectual property law in sub-Saharan Africa,” she said. At Creative Commons, she worked with local artists and attorneys to adjust the Creative Commons copyright licenses to protect both parties across the boundaries of local and international laws. “Our goal was to facilitate sharing work, so we wanted to make sure the license terms were clear to everyone,” she explained.

Schultz joined the U.S. Copyright Office as counsel in 2015. There, she contributes to policy reports for Congress and serves on teams with other government agencies involved in international copyright work, as well as researching issues particularly pertinent to Africa, such as intellectual property rights relating to traditional knowledge and folklore—songs, stories and artwork unique to a culture, with skills passed down over generations. “The international IP structure is based on personal property IP norms, so trying to fit in assets that don’t belong to a single individual is very challenging,” she said.

Old Law, New Uses

Schultz’s law school experience was vastly different from that of Amy Everhart ’98, who had moved to Nashville from North Dakota fresh out of college planning to be a singer-songwriter and start law school. Neither the Intellectual Property Program nor the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law existed when Everhart earned her J.D., but Nashville afforded a wealth of opportunities to specialize in copyright and intellectual property law. Hired by Jay Bowen ’74 and Steve Riley ’78 (BA’74) soon after they founded a litigation boutique with a focus on IP and entertainment, she discovered a small firm was an ideal place to gain substantive experience on such frontiers as copyright infringement in the karaoke industry. “I was lucky to get to learn from lawyers with great talent,” she said. “I made it clear I wanted to do IP law from the start, and the partners started referring the trademark applications to me and involving me in IP litigation.”

As a third-year lawyer, Everhart joined a team representing three major record companies in the landmark Bridgeport Music Inc. litigation and spent the next eight years defending her clients against hundreds of rap-sampling copyright infringement claims. The case placed her on the frontier of a copyright landscape undergoing radical change due to new uses and changing technologies for music distribution. “Bridgeport was a thousand-page complaint that involved more than 500 counts of copyright infringement, and it was ultimately severed into more than 500 individual infringement cases,” she said. “I cut my teeth on that case. I had a chart, and the plaintiff’s side had a chart—and each case was a line on the chart.” Only one of Everhart’s cases, involving a pre-1972 sound recording used by the rapper P. Diddy’s record label, went to trial.

Everhart started her own practice, the Everhart Law Firm, in 2009. Today she relishes working with creators and entrepreneurs seeking to establish trademarks and safeguard their work. While the digital revolution will inevitably spark copyright reform, she points out that copyright is only one of many areas of law outpaced by technological advances—and she believes it has held up better than most. “In law school, we were just starting to use email, and I didn’t use the internet for legal research,” she said. “During my career, I’ve seen the music industry completely change, and it’s amazing that the 1976 Copyright Act has been as flexible as it is. But copyright reform that addresses the creative industries as they exist in this quickly advancing world is certainly needed.”

Copyright experts Gervais and Fishman both predict that domestic and international reforms are on the horizon, and both advocate policies that protect and encourage professional creators. Gervais recommends a flexible approach that works across international boundaries and can easily be adapted to new ways to deliver creative content. Fishman supports clear guidelines that foster rather than stifle creativity. Both hope juries won’t continue to blur the lines of copyright law.