The idea of someone transitioning from black to white, without science or surgery, seems hard to grasp. Yet Associate Professor Daniel J. Sharfstein finds that, throughout American history, African Americans have crossed the color line and assimilated into white communities, starting in the 17th century. He chronicles the history of three such families in his new book, The Invisible Line: Three American Families and the Secret Journey from Black to White, and finds that their transitions had less to do with skin color than with a community's willingness to look beyond race.

“We talk about the great migration north of African Americans in the 20th century, but this mass migration across the color line impacted millions of people and was hundreds of years in the making,” said Sharfstein. “It’s very easy to forget this history. This process of migrating across the color line is something that falls outside of what we think of as African American history, because it’s a history that people were trying to cover up and forget as it was happening.”

“We talk about the great migration north of African Americans in the 20th century, but this mass migration across the color line impacted millions of people and was hundreds of years in the making,” said Sharfstein. “It’s very easy to forget this history. This process of migrating across the color line is something that falls outside of what we think of as African American history, because it’s a history that people were trying to cover up and forget as it was happening.”Self definition, not color, was key

Sharfstein spent almost a decade researching dozens of families that, for social, economic, safety and other reasons, chose to change their racial identity and create new lives. He found court and government records, personal letters and other archives that helped paint vivid pictures of these Americans and document their transitions.

While previous records of African Americans “passing” as whites have focused on individuals’ struggles to redefine themselves, often by leaving their homes and fabricating new identities, Sharfstein found large numbers of people who managed to defy the legal definitions of race right within their own communities. What mattered most, he discovered, was not the color of their skin, but how they defined themselves and related to their neighbors.

“What this research tells us is that the categories of black and white have never been about blood," Sharfstein said. "There were plenty of people throughout American history who were not just white, but quintessentially white, powerfully white, and had African American ancestors. Then we’re left thinking, ‘What is black and what is white then, if it’s not about blood and biology?’ And what we wind up with is just the fact of separation and hierarchy.”

Three families’ stories

Three families’ stories

Sharfstein focused much of his research on three families whose histories he has chronicled in The Invisible Line: Three American Families and the Secret Journey from Black to White, just released by Penguin Press.

Each of these families moved across the color line from different social positions. The Gibsons were wealthy landowners in the South Carolina backcountry who became white in the 1760s. The family ascended to the heights of the Southern elite; a member was ultimately elected to the United States Senate. “In a way, it didn’t matter that they had once been free people of color,” said Sharfstein. “What mattered was that they were planters.”

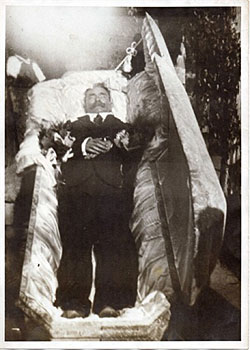

The Spencers were farmers in an Appalachian community in the hills of eastern Kentucky in the mid-1800s. The area was essentially a permanent frontier, and neighbors relied heavily on each other. Though Sharfstein found information that inferred that the family patriarch had dark skin, neighbors were fighting so hard to survive that they didn’t focus as much on color. “Periodically, decade after decade, there were moments when someone would get mad at one of the Spencers or someone didn’t like that the Spencers were marrying into another family, and the accusation that they were black would bubble up to the surface,” said Sharfstein. “Then almost immediately it would go back under the surface.”

The Walls were fixtures of the rising black middle class in post-Civil War Washington, D.C., and made the transition to white at the beginning of the 20th century. Read an essay by Professor Sharfstein about Orindatus Simon Bolivar Wall published in Slate.

Their stories uncover a forgotten America in which the rules of race were something to be believed, but not necessarily obeyed. Sharfstein uses these families, who defined themselves first as people of color and later as white, to provide a lens for understanding how people thought about and experienced race and how these ideas and experiences evolved—and the very meaning of black and white changed—over time.

– Amy Wolf, Vanderbilt University Public Affairs

Randall Lee Gibson, 1870s, after his election to Congress from Louisiana. (Image courtesy Library of Congress)

Randall Lee Gibson, 1870s, after his election to Congress from Louisiana. (Image courtesy Library of Congress)

Hart Gibson in Confederate cavalry uniform. (Image courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio)

William Jasper Spencer, Jordan Spencer’s youngest son, in his casket, Johnson County, Kentucky, 1937. (Image courtesy Freda Spencer Goble)

Logging in a mountain hollow, Johnson County, Kentucky. (Image courtesy Val McKenzie)

Stephen R. Wall of Rockingham, O.S.B. Wall’s owner and father. (Image courtesy J.D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi)

Orindatus Simon Bolivar Wall, in Joseph T. Wilson, The Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers of the United States (1890). (Image courtesy Ohio Historical Society)

Orindatus Simon Bolivar Wall, in Joseph T. Wilson, The Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers of the United States (1890). (Image courtesy Ohio Historical Society)