In the latter half of the 20th century, landmark U.S. environmental laws were passed with overwhelming bipartisan majorities—the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, the Clean Water Act in 1972, and the Clean Air Act Amendments in 1990. This statute-driven era reflected a top-down model of governance, positioning the United States as a bellwether in global environmental policy. Today’s policy landscape looks markedly different. With gridlock at the federal level, environmental governance now emerges in waves of top-down statutes and increasingly influential bottom-up initiatives as the world’s governments, corporations, and citizens contest the future direction of environmental law.

Vanderbilt Law’s Energy, Environment & Land Use (EELU) Program and Environmental Law & Policy Annual Review (ELPAR) hosted John Cruden for the 2025 Distinguished Lecture on Climate Change Governance. The event was presented by EELU Faculty Co-Directors Michael P. Vandenbergh and J.B. Ruhl and made possible by the Sally Shallenberger Brown EELU Fund.

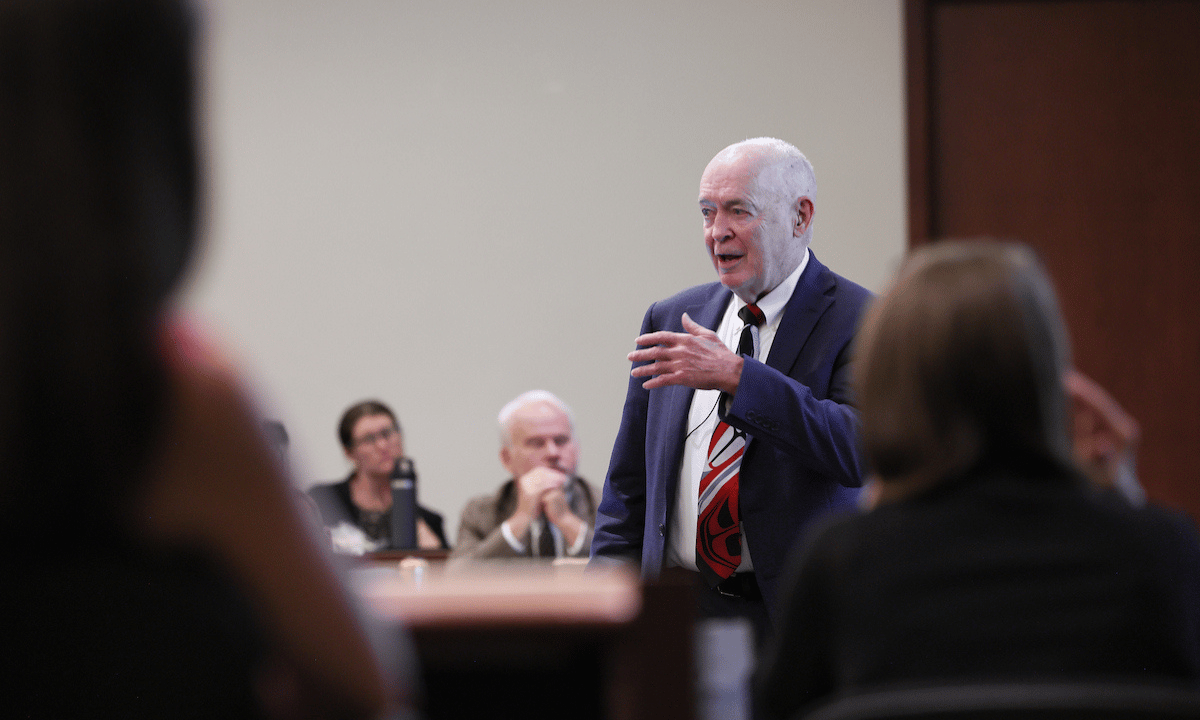

Mr. Cruden is Principal at Beveridge & Diamond, P.C., where he advises clients on high-stakes environmental litigation, enforcement, and compliance matters. He previously served as Assistant Attorney General for the Environment and Natural Resources Division (ENRD) at the U.S. Department of Justice, where he led landmark cases including the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the Volkswagen emissions scandal. His four-decade career spans service as Chief Legislative Counsel of the U.S. Army and combat duty in Vietnam, senior leadership at ENRD, and presidency of the Environmental Law Institute.

The Origins of Modern Environmental Law

Cruden tied the birth of modern U.S. environmental legislation to what he called “Cuyahoga moments”—highly visible crises that galvanized public awareness and political response. The term references the 1969 Cuyahoga River Fire caused by the river being so densely polluted with industrial waste that it ignited. It represented the first of a series of environmental disasters that sparked national outrage and laid the groundwork for the Clean Water Act, which Congress enacted over President Richard Nixon’s veto.

“A lot of our statutes were born of tragedy,” Cruden noted. Love Canal’s toxic contamination prompted the creation of Superfund, the Exxon Valdez oil spill led to the Oil Pollution Act, and deadly widespread smog accelerated the Clean Air Act. These events, he argued, defined an era when bipartisan consensus enabled sweeping legislative reforms. For nearly two decades, this “top-down” approach positioned the United States as the global leader in environmental governance. Congress, the courts, and newly created agencies—most notably the Environmental Protection Agency—worked in tandem to build a comprehensive statutory framework.

“The United States didn’t actually create much law in our lifetime. We got most of it from the Greeks and Romans and Brits,” he said. “There is an exception—we created environmental law without question. The body of law that people talk about as environmental law, it came from the United States. Now 93 percent of the countries in the world have something that looks like our National Environmental Policy Act.”

From Top-Down to Bottom-Up Governance

After the golden era of bipartisan statute-making ended in 1990, the top-down model for environmental governance effectively ended. Congressional gridlock has since prevented passage of major statutes, even as new challenges and climate social movements have emerged.

Cruden described a shift in governance toward bottom-up approaches, driven by state initiatives, corporate policies, and international frameworks. He pointed to reform of the Toxic Substances Control Act as a key example. This effort not originate in Congress, but from mounting pressure at other levels of governance. Eighteen states enacted their own chemical safety laws to protect air and water, filling what he described as a regulatory vacuum. At the same time, international developments exerted influence, particularly the European Union’s adoption of REACH—more expansive and stringent than U.S. law. “Out of the state issues, out of a little Cuyahoga moment, out of what was happening internationally, there became a consensus for change,” he explained.

“I’m thinking this is a ‘bottom-up’ because Congress tried and failed. But what happened? People underneath them, people like me and you, corporations but also NGOs and runway groups, they then were responsible for change.”

Watch the full discussion here or on our YouTube Channel:

The Role of Technology and Private Governance

New tools and technologies—ranging from drones and satellites to low-cost air and water testing kits—are reshaping environmental governance by transforming how pollution can be monitored and enforced. “For a relatively small amount of money now, you can get testing data for both air and water that is pretty accurate,” Cruden noted, adding that these tools empower citizens to hold agencies and corporations accountable. “That actually drives up interest and perhaps creates the kind of momentum we need for the future.”

Private governance is augmenting the influence of corporations in driving environmental and climate action. Contrary to widespread public criticism, Cruden argued that multinational companies are shaping greener outcomes through supply chains and contracting practices. Walmart, for instance, can compel thousands of suppliers to adopt stricter environmental standards simply as a condition of doing business. CEOs at firms like DuPont and Johnson & Johnson have invested in greener product design and efficiency measures to align with consumer demand. But Cruden cautioned that corporate action is not a substitute for public law. “Two-thirds of America still believes corporations are not doing enough,” he said, emphasizing that private commitments must complement statutory enforcement and work in coordination with regulators, NGOs, and international frameworks.

Passing the Baton

The next phase of environmental law demands effective advocates who know how to frame issues in ways that resonate with both the public and policymakers, Cruden said. He pointed to the Montreal Protocol as an example of bipartisan success, where leaders like George Shultz and President Ronald Reagan framed action on ozone depletion as an “insurance policy,” a phrase that diffused debates and built trust, negotiation, and consensus.

“If there is a Cuyahoga moment, are you ready?” he asked students. “We need good communicators if we’re going to do bottom-up.”

Looking ahead, he outlined the building blocks of the next era of governance. For students entering environmental law, the future will be defined by crisis-driven opportunities, and rapid public response will open windows for reform. Statutes and enforcement remain essential, but progress will increasingly depend on the interplay of state leadership, citizen engagement, corporate responsibility, and international standards. New technologies will only be effective if paired with legal frameworks and political will.

“I want you to be knowledgeable out there. I want you to study. I want you to be able to communicate,” Cruden said. “I’m asking you to know and understand and be able to talk about why we have billion-dollar events occurring, why we have sea levels rising, why we have fires everywhere, why all of that is occurring. I’m getting to the point of my life where I’m ready to pass the baton.”