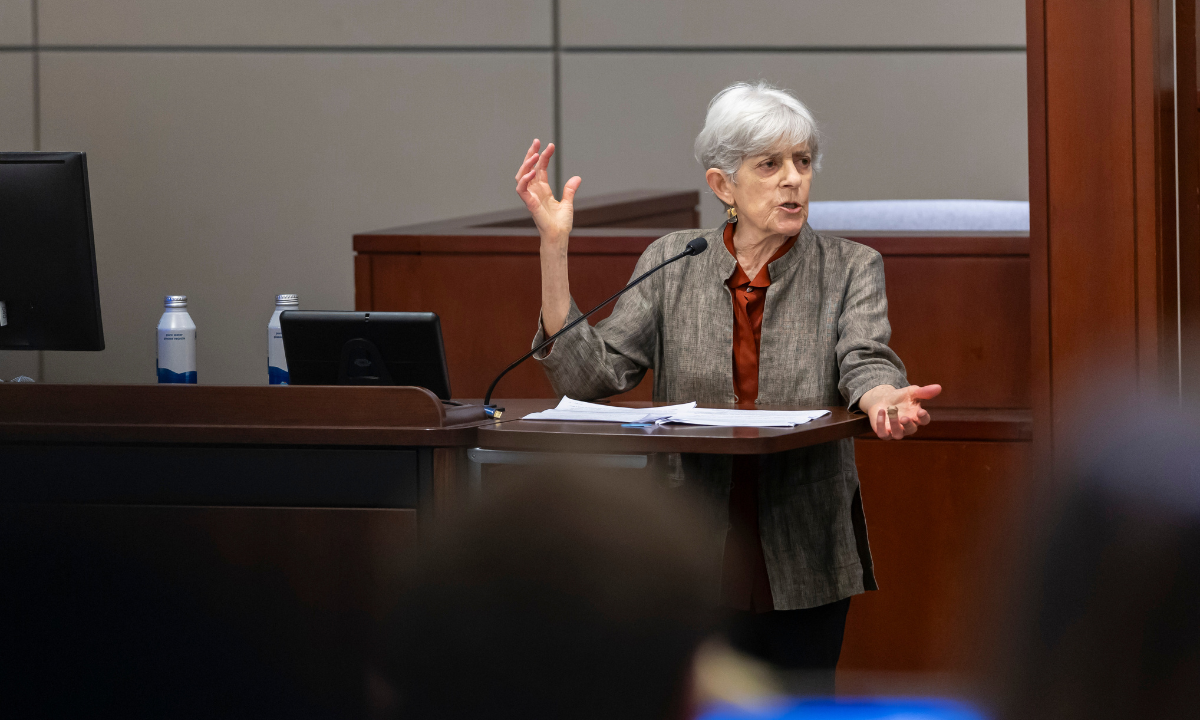

Last month, the Women, Law, and Policy Program at Vanderbilt Law welcomed historian Nancy Cott to campus for a lunchtime talk titled “Doctors, Lawyers, and Feminists on the Road to Roe v. Wade.”

Cott is the Jonathan Trumbull Research Professor of American History at Harvard University. Her talk focused on her recent research around the fight for women’s reproductive rights and the history of abortion in the United States, from the late 19th century through the 20th century, culminating in the Roe v. Wade decision.

Cott began with a discussion on the initial attempts to ban abortion through state legislation, spearheaded by Boston gynecologist Horatio Storer. In the mid 19th century, through much of the United States, abortion was legal up until the woman began to feel a fetus move inside of her, known as quickening. Storer believed that all abortions should be prohibited unless they were deemed medically necessary to save a mother’s life.

“When he rallied positions around him to a campaign in the late 19th century, he was not only making that medical point, but he was decrying women who would have abortions by using both sexist and ethnically prejudiced language about what use of abortion meant,” Cott said. “This really had legs among other doctors, who, like him, were basically white and Protestant.”

Storer and his supporters compelled the recently founded American Medical Association to recommend to every state legislature and governor that abortion be criminalized. Across America, abortion became illegal except in cases where it was necessary to save a woman’s life. The shift gave rise to illegal abortions.

“Access to a safer illegal abortion really depended on where (a woman) lived, what her information networks were, and rather crucially, her ability to pay, because illegal providers used to charge very high fees,” explained Cott.

In May 1959, a recommendation from the American Law Institute (ALI) expanded abortion access. This recommendation allowed abortion under three prongs: if the pregnancy posed substantial risks to a mother’s physical or mental health; if the child would have grave defects; or if the pregnancy resulted from rape, incest, or other felonious intercourse. This recommendation was picked up by many doctor advocates across the nation who tried to get it instituted in legislation.

“[A] few doctor reformers were paying attention, and they were very heartened by the ALI reform law, and they started using it,” Cott said. “In fact, it gave them a lot of credibility, and several of them reached legislatures in potential states and started trying to get bills before [them].”

Many states instituted the ALI reform law, in full or partial form. This access increased what Cott referred to as the “public appetite for better access to abortion.” Feminist rights movements started forming a grassroots movement for the expansion of abortion, insisting that no woman should have to bear a child that she was unwilling to bear. As Cott described it, the 1973 Supreme Court decision in the case of Roe v. Wade legitimized these arguments of the feminist movement while accounting for the doctors’ movement that initially criminalized the practice. The Court struck a middle ground on the issue, providing certain regulations regarding second and third-trimester abortions.

Cott argued that Americans can draw on this history to navigate the current state of abortion rights in the United States.

“Today’s patterns of abortion access and advocacy [are] different [from] then, but I think we can learn from it,” Cott said. “Doctors, I suspect, will have to continue to be central to any effort, but as a professional group, they may not be as effective as they once were. It is multi-pronged efforts by varying groups who may not be united, but who are all working over many years and gathering facts about the situation will be likely drivers of change.”