Daniel Gervais’ book sheds light on the provisions of a complex agreement.

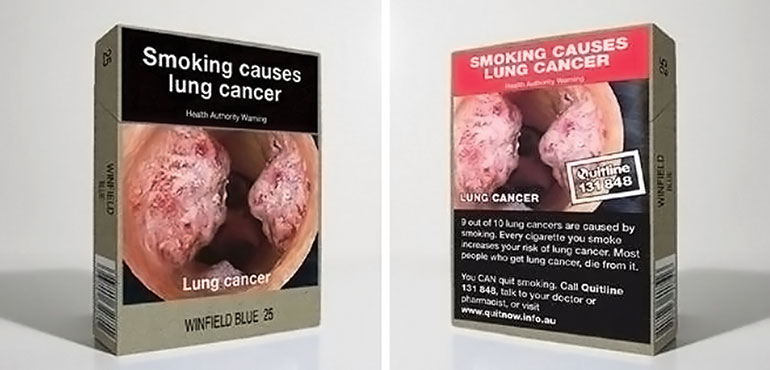

You won’t find pictures of cowboys, camels or kangaroos on cigarette packs in Australia these days. The country’s Plain Packaging Act is clearly intended to discourage smoking. Cigarettes sold in the Land Down Under now come in drab olive boxes emblazoned with warnings about smoking’s health risks accompanied by graphic photographs of diseased body parts. The use of familiar brand colors, typefaces and logos is prohibited.

“This packaging makes everybody’s product look generally the same,” said Daniel Gervais, director of Vanderbilt’s Intellectual Property Program and the FedEx Research Professor of Law.

But is that prohibition legal?

Philip Morris challenged the law in Australia’s High Court, claiming that the Plain Packaging Act violated its intellectual property rights and was unconstitutional. The High Court rejected that claim in August 2012, and the new packaging debuted in December.

However, Australia’s High Court may not have the last word in this dispute. The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS, allows countries exporting tobacco products to Australia to challenge the provisions of the Plain Packaging Act before a dispute-settlement panel convened by the World Trade Organization. Article 20, Section D, of the agreement states: “The use of a trademark in commerce shall not be unjustifiably encumbered by special requirements, such as…use in a special form or use in a manner detrimental to its capability to distinguish the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings.”

Two countries have filed cases with the WTO challenging the Plain Packaging Act. “Ultimately, the act’s fate will depend on how the three-member WTO panel—and possibly the WTO Appellate Body if an appeal of the panel report is filed—interprets TRIPS’ trademark provisions, in particular Article 20, Section D of the agreement,” Gervais said. “People are following this dispute really closely, because it will impact many other parts of the international IP picture.”

TRIPS, which became effective in 1995, established a permanent, cooperative relationship between the World Intellectual Property Organization and the WTO, which administers the agreement. Under TRIPS, countries file disputes with the WTO, which has an international dispute-settlement system to adjudicate them. As a result, WTO panels effectively function as a “court” of last resort for international intellectual property disputes. “The TRIPS Agreement established minimum standards for the treatment of intellectual property internationally, and it remains the most comprehensive multilateral agreement on intellectual property to date,” said Gervais, one of the world’s foremost TRIPS authorities. “The interpretation of the TRIPS Agreement is crucial to all cases involving international intellectual property rights.”

Gervais has a unique historical perspective on TRIPS. He was present in the early 1990s as the complex agreement was negotiated under the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. As a member of the WTO/GATT legal staff, he supported representatives from several countries as they hammered out the provisions of the new agreement. The need for a detailed commentary to help lawyers interpret TRIPS’ complex provisions immediately became clear to Gervais. “I was in the room as a member of the secretariat that was facilitating the discussion, heard the issues that were raised, and understood how and why the rules in the agreement had been established,” he said. “I knew that lawyers and judges would need to understand the original intent of the TRIPS rules and how those rules were arrived at.”

The first edition of Gervais’ definitive book on the TRIPS Agreement was published in 1998. It offered a careful history of the agreement’s development and inception, highlighted important compromises negotiated to establish TRIPS, and provided a detailed commentary on each section of the agreement. In two subsequent editions, Gervais added discussions of important TRIPS disputes and their resolution. The fourth edition, The TRIPS Agreement: Drafting History and Analysis, released in 2012, includes a new grid that shows the differences between the rules each nation originally hoped the agreement would incorporate and the actual provisions of the final agreement.

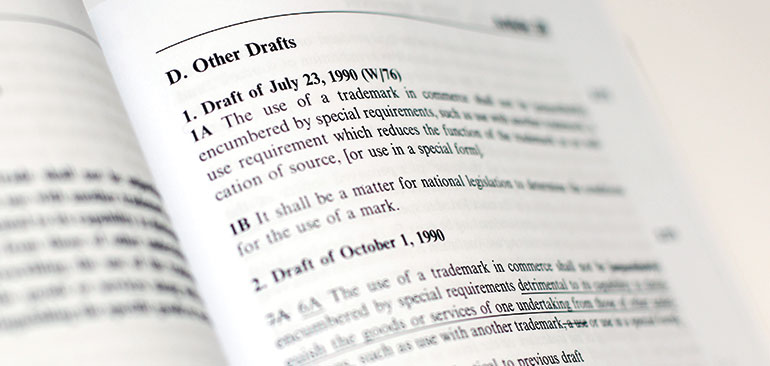

Gervais also added a comprehensive drafting history of the agreement, based on his observation that some WTO panels were using earlier drafts of the agreement to help interpret its provisions. “Members of WTO panels had access to the earlier drafts, but the attorneys appearing before them didn’t,” Gervais said. “I felt that all members of the WTO should have access to these drafts.”

Understanding TRIPS’ drafting history should help lawyers preparing for WTO panel hearings that address laws like Australia’s Plain Packaging Act, according to Gervais.“The new packaging Australia requires is detrimental to Marlboro’s ability to distinguish its cigarettes from Camel, and many observers believe the Plain Packaging Act definitely presents an encumbrance under Article 20,” he said. “So the case may hinge on whether Australia’s goal—to reduce sickness and deaths caused by smoking and the costs of treating smoking-related illnesses—justifies requiring standardized packaging that functionally eliminates brand trademarks and logos.

“When you look at the drafting history of Article 20, Section D, you’ll find that were three drafts of this provision,” Gervais continued. “In the earliest draft, the word ‘unjustifiably’ is in square brackets. In the second draft, it’s deleted. And in the third, it’s reinstated. That means that the drafters of the agreement thought very hard about whether to include the word ‘unjustified’ in the agreement. That word is not typical in international intellectual property, and the dispute settlement panel will probably be called upon to establish the proper ‘justification’ burden.”

Gervais has also established and edits a website devoted to TRIPS at www.tripsagreement.net.